Ah, the sucking chest wound—one of trauma’s most dramatic party tricks. If you’ve ever heard a patient’s chest literally sucking air like a punctured tyre, congratulations! You’ve just encountered one of the most dangerous thoracic injuries in prehospital care.

A sucking chest wound (SCW) isn’t just a cool name—it’s a gaping hole in the chest that allows air to rush into the pleural space with every breath. The result? A collapsing lung, increasing pressure, and a potential descent into respiratory and cardiac failure.

Let’s break it down.

What Is a Sucking Chest Wound?

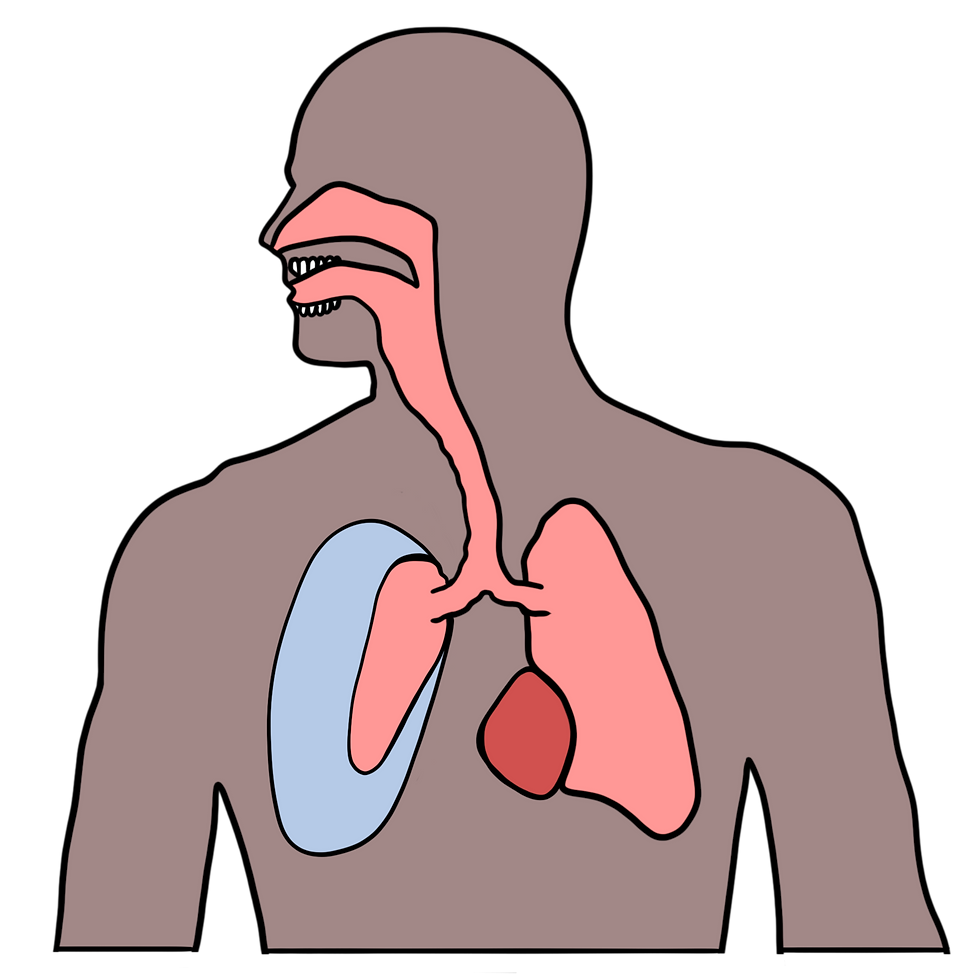

A sucking chest wound (SCW), also known as an open pneumothorax, is a penetrating injury to the chest wall that creates an open pathway for air to enter the pleural cavity. Instead of air going into the lungs where it belongs, it escapes into the pleural space, leading to a lung collapse (pneumothorax).

If left untreated, it can rapidly progress to a tension pneumothorax, which is the fast track to cardiac arrest.

🩸 Common causes include:

✅ Gunshot wounds – A classic, but not exclusive, cause.

✅ Stab wounds – Knives, broken glass, or anything else that impales a chest wall.

✅ Blast injuries – Shrapnel, debris, or blunt trauma causing penetrating damage.

✅ Surgical mishaps – Post-op chest tube removals or complications from medical procedures.

What a Sucking Chest Wound Does to the Body

Think of your chest cavity like a sealed vacuum—when intact, air only goes where it's supposed to (into the lungs). When punctured, things go catastrophically wrong:

1️⃣ Air enters the pleural space on inhalation instead of going into the lungs.

2️⃣ The lung collapses due to the increasing pressure inside the chest.

3️⃣ Less oxygen reaches the blood, leading to hypoxia.

4️⃣ The pressure can build up, leading to a tension pneumothorax—a life-threatening shift of the mediastinum that compresses the heart and major vessels.

🚨 Signs & Symptoms of an SCW 🚨

🛑 A visible open chest wound (bubbling or making sucking noises).

🛑 Shortness of breath (dyspnoea) – Rapid, shallow, and laboured breathing.

🛑 Sucking or gurgling sounds from the wound.

🛑 Frothy blood at the wound site (air mixing with blood).

🛑 Decreased or absent breath sounds on the affected side.

🛑 Tracheal deviation (late sign) – A sign that things are going downhill fast.

🛑 Cyanosis & worsening hypoxia – The patient is running out of oxygen.

If you don’t intervene, things escalate rapidly into tension pneumothorax and cardiovascular collapse.

Why Is a Sucking Chest Wound a Problem in PHTLS?

In Prehospital Trauma Life Support (PHTLS), SCWs are high priority for several reasons:

1️⃣ Immediate threat to life – Even if the patient seems “OK” initially, their condition can deteriorate in minutes.

2️⃣ Tension Pneumothorax Risk – If air keeps entering the pleural space without a way to escape, the pressure will eventually crush the lungs, heart, and great vessels.

3️⃣ Difficult Airway & Oxygenation Issues – Patients may struggle to breathe, leading to hypoxia, shock, and death if untreated.

4️⃣ High Index of Suspicion – If there’s a penetrating chest wound, assume it’s an SCW until proven otherwise.

This is not a "wait-and-see" situation—early intervention is key.

How to Manage a Sucking Chest Wound in PHTLS

When faced with a sucking chest wound, follow these steps:

1. Immediate Wound Sealing (Chest Seal Application)

Use a vented chest seal if available (Halo, HyFin, or Fox chest seals are ideal).

If no commercial seal is available, an occlusive dressing (e.g., plastic wrapper, glove, or foil) can be temporarily used.

Secure on three sides, leaving one side open to allow air to escape (prevents tension pneumothorax).

2.Monitor for Worsening Symptoms

If the patient deteriorates after sealing the wound, a tension pneumothorax may be developing.

In this case, burp the seal (lift one side to allow trapped air to escape).

3. High-Flow Oxygen

Administer oxygen (via mask or nasal cannula) to counteract hypoxia.

Assist ventilation if needed (be cautious with BVM—avoid over-pressurising the lungs).

4. Needle Decompression (If Indicated & Allowed by Protocols)

If the patient is showing tension pneumothorax signs (tracheal deviation, absent breath sounds, hypotension), a needle thoracostomy (14-16 gauge needle into the second intercostal space, mid-clavicular line) may be necessary.

Only perform if trained and authorised—otherwise, focus on rapid transport.

5. Rapid Transport to Trauma Centre

This is a load-and-go scenario—chest trauma patients need definitive surgical care ASAP.

Warn the receiving hospital of a potential tension pneumothorax risk.

Final Thoughts

A sucking chest wound is one of the fastest ways a trauma patient can die if not treated properly.

🚑 Key Takeaways for PHTLS Medics:

✅ Recognise an SCW immediately – If there’s an open chest wound, assume air is entering the pleural space.

✅ Seal the wound quickly – Use a vented chest seal or improvised occlusive dressing.

✅ Monitor for tension pneumothorax – If the patient deteriorates, burp the seal or perform decompression if trained.

✅ Oxygenate & Transport ASAP – Definitive care = surgery, so get them to a trauma centre fast.

Remember: Air goes in, but it shouldn’t go in through the chest wall. Fix that problem, and you just might save a life.

Stay safe, Kraken Medics – and keep the air where it belongs. 🚑💨

Further Reading & Useful Resources

🔹 NHS: Chest Trauma Guidelineshttps://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pneumothorax/

🔹 Resuscitation Council UK: Chest Trauma Airway Managementhttps://www.resus.org.uk/library/airway-management

🔹 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) – Pneumothorax Managementhttps://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng115

🔹 BMJ: Prehospital Management of Thoracic Traumahttps://bmj.com/content/thoracic-trauma

🔹 Prehospital Trauma Life Support (PHTLS) Manual – Chest Trauma Guidelineshttps://www.naemt.org/education/phtls

Commentaires